- Stay Connected

Agencies can learn from starved boy’s tragic death, inquest told

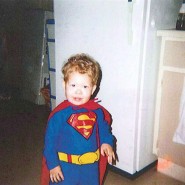

Jeffrey Baldwin is shown in a Halloween costume in this undated handout photo released at the inquest into his death. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO - Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario

Allison Jones, The Canadian Press

TORONTO - A five-year-old boy who starved to death in his grandparents’ Toronto home didn’t just slip through one crack, but through a whole institutional safety net, lawyers at a coroner’s inquest suggested Tuesday.

The jury at the inquest into the death of five-year-old Jeffrey Baldwin heard dozens of proposed recommendations aimed at various ministries and agencies during closing submissions.

The suggestions, which the jury can choose whether to adopt as part of its verdict, pointed to more than just one reason that Jeffrey died severely malnourished, unable to lift his own head, locked in a cold, putrid bedroom. Rather, they indicate a constellation of institutional and personal failures.

“Jeffrey Baldwin received far more attention after his death than he ever did in his life,” said coroner’s counsel Jill Witkin as she presented 74 recommendations jointly suggested by various groups with standing at the inquest.

“Tragically, as you know, he was not given the freedom and opportunities that children in our society deserve. He died as a child neglected by his caregivers and shielded from the organizations out there that could protect him.”

The recommendations — which included using Jeffrey’s story as a case study for training children’s aid workers, implementing better information sharing across agencies involved with child protection and starting a public awareness campaign about people’s duty to report suspected child abuse or neglect — can help prevent deaths like Jeffrey’s in the future, Witkin said.

Jeffrey’s grandparents, chiefly his grandmother Elva Bottineau, had custody of the boy and his three siblings, first from children’s aid then Bottineau successfully applied to make it permanent through family court. But Jeffrey and one of his sisters were treated very differently than the others, neglected and starved, reduced to drinking toilet water. His sister may have only survived, the inquest heard, because she was allowed to go to school, where she was given a small snack every day.

Both grandparents had previous convictions for child abuse when they were granted custody of Jeffrey and his siblings, but that wasn’t discovered in the Catholic Children’s Aid Society’s own files until after Jeffrey’s death.

It has been more than 11 years since Jeffrey died, and it’s tempting to think that in that time all of the necessary policy and legislative changes have been made, said Freya Kristjanson, a lawyer for Jeffrey’s siblings.

“Sadly, I suggest that the evidence shows that while many commendable changes have been made, and some of them directly in response to Jeffrey’s death, much more needs to be done,” she told the jury. Gaps remain in information sharing systems between child protection agencies, she said, and testimony suggested some of Jeffrey’s sister’s teachers were unaware of their duty to report suspected abuse or neglect to children’s aid.

But one area in which it’s impossible to make recommendations, Kristjanson said, is in regards to the other adults who were living in that home and did nothing to save Jeffrey. Elva Bottineau, Norman Kidman, two of their adult daughters — not including Jeffrey’s mother — and the daughters’ partners made up the six adults under that roof.

One aunt testified she “didn’t pay that much attention” to Jeffrey and his condition, which experts say would have been immediately apparent and shocking to any person. Her partner told the inquest last year that he did notice Jeffrey’s slow decline and was “bugged” by it, but didn’t want to create friction by reporting it.

“You cannot legislate humanity, compassion, basic human dignity and decency, and that is why we make no recommendation in that regard,” Kristjanson said.

“Frankly we don’t think there’s anything this jury can say to make a difference for those kinds of people. That is why our recommendations are collectively focused at the institutions that…have oversight over those people.”

For her part, Bottineau sneered, rolled her eyes and talked throughout Kristjanson’s submissions about the “horrors” of Jeffrey’s treatment and his “sadistic” family.

Bottineau asked for standing part of the way through the inquest and is watching via a screen from the prison where she is serving a life sentence for second-degree murder. Her screen is muted in the inquest room, but Bottineau could be seen giving the screen a hard stare while Kristjanson was talking, and appearing to respond angrily to the submissions.

At one point she threw her hands up in the air, then sat with her arms crossed, staring up at the ceiling.

The inquest wasn’t held until 11 years after Jeffrey’s death because Bottineau only exhausted all of her appeals in 2012.

The coroner’s inquest is not looking to assign blame, but rather explore systemic issues surrounding Jeffrey’s death. The jury can make recommendations aimed at preventing such situations in the future.